the bigfoot proof

An account of my Bigfoot 200.

Acknowledgments

At the start of this writing I must acknowledge my father who was there for me at the start of the race, there well before the start, and there at all the key points along the way. He has long supported me in my wandering adventures. My dad is a bit of a dreamer. I’ve got a lot of that too. But we don’t just dream. We also attempt to live out our adventures. Particularly dear to my heart was his first time crewing me in my first one-hundred back in June 2015 at the San Diego 100. There he helped nurse me back from the pits of dehydration and despair and provided the perfect mix of compelling and comforting encouragement.

I was ecstatic when he told me prior to this race that he would be completely available for me throughout the long weekend. From merely a logistical standpoint his presence would remove any requirement for me to deal with the stress and complexity of planning and prepping drop bags for the various aid stations. Then he drove me the hours to the pre-race festivities, a big pre-race meal in Vancouver, and to the start the next day. Once the race started he shuttled bags of gear to every single crew-accessible aid station, separated by hours of cautious driving on winding and often washed-out mountain roads. As I arrived at an aid station he would have my gear at hand, ready to help change my socks, refill my water and gummy bear baggies, replace batteries for and test my headlamp, and coordinate the support from the wonderful aid station volunteers. While I attempted to sleep fitfully in the back of his vehicle, he forewent sleep in the front—constantly sacrificing his comforts for mine. While I had hot food prepped for me at the aid stations, he had cold food from his car. He faced the same dirty heat and wet cold that I did but without the fanfare.

All this and more that I don’t know he did for me for more than four days. While much of the race, for me, was spent alone in the woods or along the ridge lines, some of the most key points were the actions in the aid stations. He helped ensure that I cleaned my feet and put them up and that I ate and drank properly at each station. Then he helped see me off. That decision to leave for another leg was never borne lightly. When I was off enjoying the trails, he was busying gathering intel from other runners, crews, and aid station volunteers about the next leg and then helping me plan to adapt to the changing environment and our changing understanding of it and my condition. In the thick of the race he was still dreaming, scheming with me how we could do bigger and better next time. Hopefully for next time we’ll find a trail race to run together.

I thank my mother for what I do earnestly believe is an abundance of prudence that I brought to the running of this race. I thank also my family and friends who, whether they believed in me or not, never questioned my sincerity in attempting this run. I'm glad my baby brother and his friend came to support me on the first day. I hope his friends at school no longer think my doing a 200-mile race is a tall tale. I must acknowledge the amazing volunteers at the aid stations who were inspiring in many ways, the Donovan family for their inspiration and support for my crew, and the race director and her team for putting together such a wild adventure. I'm grateful for my fellow runners and am excited to follow their future adventures. I especially thank Emily for being there with me on my failure at the Kodiak 100 last year and talking me through that to a return and the adventurous success, with her crewing, at the Orcas Island 100.

Statistics

- Distance: 206.5 miles

- Elevation gain: +42,506'

- Elevation loss: -43,906'

- Finish time: 96:20:18

- Starters: 107

- Finishers: 78 (72%)

Results from UltraSignup.com

Reflections

When I finished the race I posted a picture of my belt buckle and the letters Q.E.D. Actively imagining what it would be like to finish I had settled on that quick short post early in the race. If we think back to the hazy days of high school geometry proofs we might recall it stands for quod erat demonstrandum or “what was to be demonstrated.” I figured it was a way for me to say, “See, I did it!” Over the miles and days the meaning changed for me. I still accomplished something. But now it was as though the schoolmaster was saying Q.E.D. after leading us through a particularly difficult problem. This Q.E.D. was an acknowledgment of working through the problem posed by the race director. Now I’ve got to see if I’ve learned anything from it.

A researcher studying the post-eruption succession of the ecology around Mount St. Helens has said it is a "a wonderful living laboratory" and that is just what this race was itself. This was a chance to observe myself challenge myself, observe myself amidst the heat, cold, pain, and tedium, and observe myself observing others.

On the drive to the start my face was grinning and my arms and legs were trembling—gleeful terror. All that physically manifested fear evaporated as I set about doing. I thought often of the extreme of that fear during the race. While I was still nervous when hearing sounds in the dark or when on wobbly legs over deep cliffs, I never had that same fear. Something about the starting removed it or covered it over. I'm still reflecting on the role of fear in preparing me for the race and in my life.

My goal for this race was to finish. To finish healthy. I had not put in any sleep deprivation testing or training and decided right off that I was not inclined to test out hallucinations on the sheer inclines the race director gave us.

I never confronted the sort of doubts that I lost to in the Headlands 100 or the Kodiak 100 or even those that I barely tearfully bested in the Rocky Raccoon 100 (or survived only with aid station assistance and a volunteered bag of gummy bears at the San Diego 100). Instead I dealt with the nagging concerns about hurting myself. I’m not normally one to shy away from pain. However the distance here meant that it would be all too easy to seriously aggravate minor injuries. Most every step was taken with some small circumspection—looking for anything sharp, slippery, slanted, or that might snag. Even in the lightest moments I was aware that mind over matter had its limits and the race was not entirely in my hands.

One of the great things about ultra running is the other runners. Whether by words or by deed they are always inspiring. I am often humbled by my fellow runners. What is particularly humbling is not that anyone is faster than me, but how easy it is to judge another. This race was a renewed reminder that I don’t know the journey that brings someone into my life, what they are going through, or what dreams they have. I will endeavor to bring that lesson into my life. The selfless support from the aid station volunteers and the crews were also a shining example of what I hope I can do as I cross paths with people in my daily life. While some ran without pacers and others ran without crew, no one ran without the support of their fellow runners or the aid stations volunteers and race staff. That is a lesson I hope to live and share with others.

When passing a runner moving slowly on a leg deep into the race I asked how he was doing and I believe he told no lie when he responded, “Never better.” There was pain and frustration for all the runners throughout the race, but there was also adventure and becoming. While his body surely had seen and will see better times and climes, on that climb he had the presence of mind to acknowledge and choose his intentions and attentions.

Another refrain from runners was the cheery and chary, “Have fun!” This often seemed to be said with the sincerest sarcasm. While runners may not have set out to have fun and some seriousness may have rightfully consumed their quest, the pumping of one’s legs and lungs through such beautiful and beastly terrain has a way of producing a grim smile if not some moments of unquenchable joy.

I have more lessons I’m working through still. Lessons of cowardice. Lessons from Melville pried from and plied to the run. More lessons on confidence markers. I hope also to review and reflect on my prior race reports and see what I missed or am missing.

I am not done with the Bigfoot 200 and it is not done with me. That is not merely clichéd language about a dreamt-of return in 2018 but an acknowledgment of the persistence of the race. Even as I ran that race with memories of my past, I will rerun this race many times to come. As the schoolmaster says in vain and the race director needn’t ever say: you will use this in your life.

Leg by Leg

While one stills runs a race of this distance step by step, leg by leg seems to be a productive way to break it down, both as a runner confronting it and in reflection.

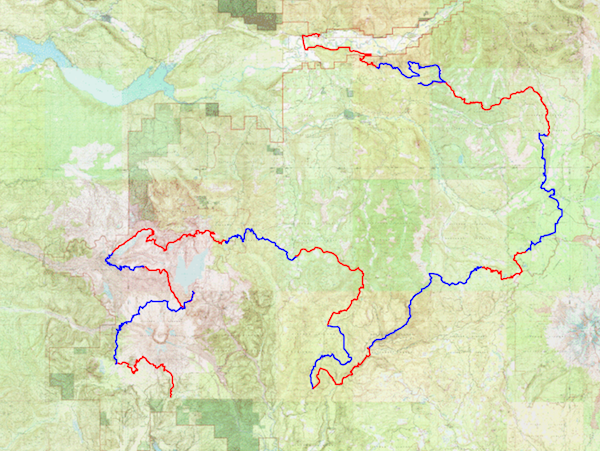

A minimally-detailed map of the course: starting at the bottom of the map south of Mount St. Helens and ending at the top of the map in Randle, WA. The full map of the 2017 course is publicly provided by Destination Trail for the Bigfoot 200 at CalTopo and linked to from the Runner's Manual.

Marble Mountain to Blue Lake: 12.2 miles +3,280' -2,743'

Day 1: Starting at 0900 (temporally) and 5:40 (spatially with respect to Mount St. Helens) on Friday morning, 106 of us squeezed onto the trails and I fell into a relaxing, though perhaps too quick, pace. We snaked through the trees and then over boulders before winding back down to Blue Lake—completing our first leg clockwise around the mountain.

A bit of the boulders and me (Howie Stern & Scott Rokis Photography).

Blue Lake (~8 o’clock spatially) to Windy Ridge (~1 o’clock): 18.1 miles +4428' -3166'

A view of Mount St. Helens through the trees.

The heat started to bear down as we gradually moved out of the trees onto the desolated pumice plain created from the pyroclastic flow 37 years ago. We ascended into and out of small canyons with fixed ropes and trudged through varying arid and exposed terrain, over silt-ridden rivers and along sandy hillsides.

Image of my leaping over a small stream in the small canyon in tore into the pumice plain (Howie Stern & Scott Rokis Photography).

Then a long slog up a gravel road on Windy Ridge to the second aid station. I had stopped for water at a river in the trees, and then a silty river and pure spring on the plain and was clearly suffering a bit from the heat but was generally focused though not quite upbeat. This was a non-crew aid station so I didn’t spend much time and turned back around to head out onto the short and minimal elevation change third leg.

Windy Ridge to Johnston Ridge: 9.6 miles +1567' -1487'

The view of the crater.

My attitude quickly turned as heading out I realized I had some cell service so sent a couple messages, started listening to an audiobook of Melville’s Moby Dick, and saw the tremendous crater before me as we went back down the ridge. The book starts right off with some words grasping at why people seek out the sea or other bodies of water and I was reminded of why I run. The biggest grin returned to my face. I was seeking that “the ungraspable phantom of life”.

Heading away from Mount St. Helens, a view of Spirit Lake.

Image from Johnston Ridge of myself running and the crater dominating the background (Howie Stern & Scott Rokis Photography).

As evening slowly fell, still struggling from the earlier heat, I moved counterclockwise now farther from the mountain and towards a point just short of the observatory. My father met me and we changed out my socks, cleaned my feet, and I set off again.

Johnston Ridge to Coldwater Lake: 6.6 miles +412' -2099'

I gratefully turned back after ten feet to grab my hiking poles, which I nearly forgot. Darkness fell and we dropped down to the lake on an easy trail. I came into the next station well ahead of schedule. Met my dad for a change of short, shirts, and socks and, with an abundance of prudence and the race director’s words about the next long leg (“Best views of the course, recommend running in daylight if possible.”), I bedded down for several hours. I was only 46.5 miles in but I tossed and turned in the provided tent, attempting to adjust for my sore legs, the cold, and mosquitoes. Without really any solid sleep I began again at 3am.

Coldwater Lake to Norway Pass: 18.7 miles +5105' -3909'

Day 2: I set out in the dark along the lake, horribly frightened at one point by a loud splash from some large animal dropping into the water from just off the trail. This route gradually turned to rough and heavily overgrown switch backs up to the ridges. I held up my hiking poles to clear the vegetation from my face and plunged through.

The depths from which we climbed.

The trail came out on some breathtaking views.

Another view of the crater.

I happened upon service again and shared some smiley selfies.

A view of the crater and my face.

Stunning views as the sun rose.

I again used poles to help traverse patches of snow.

A view of the crater from Mount Margaret.

After the short but steep Mount Margaret out-and-back, the trail looped around, heavily exposed, down to the next aid station. This is where the heat really started to bring about some chafing in my nether region. I will not be delicate about this because it was not delicate to me. I was horribly hobbled and perplexed as I hadn’t struggled with anything of the sort since my first marathon nine years ago. But, I’ll get back to this. Mount Margaret was the high point of the course and so the race director lied to us in the runner’s manual: “it’s all downhill from here!” I did enjoy sitting for a bit at this aid station, especially the frozen popsicle provided by the volunteers.

Norway Pass to Elk Pass: 11.1 miles +2037' -1558'

This shouldn’t have been too bad, but the heat was increasing along with the pain in my groin and my fear of being unable to adequately cope. I’d read race reports from years prior of runners finding themselves with significant chafing-induced injuries that built up over the scores of miles and was already seeing its effect on me throughout this leg. I climbed over and around logs from the still recovering blast area and then wound through forested areas that provided some safety from the sun. This next aid station I changed shorts again, and tried my third type of remedy, desperate for some reprieve. With my father’s help I headed out onto the next section.

Elk Pass to Road 9327: 15 miles +2543' -3144'

This segment seemed interminably long as I recklessly played with my gait to adjust for the pain, but the views were incredible.

A clear view of Mount Rainier.

A view of Mount Rainier—"the most prominent and glaciated peak in the contiguous United States".

Night fell again and I arrived at the next aid station hopeful that significant rest might alleviate the concern that was foremost in my mind. I ate some food and tucked myself into the back of my dad’s vehicle. I knew I had to resolve the chafing. My pain-induced pace change would not but barely get me across the finish line (I was only 91.3 miles in) and even then I wondered at what the pain or injury might become after two more days. I slept sloppily aslant in the rear of the vehicle constantly sliding onto the pained pads of my feet. When the alarm went off it was pouring down rain. Normally I don’t fear rain but I knew it might wreak havoc on my injury so I attempted sleep for another hour and set off at 5am.

Road 9327 to Spencer Butte: 11.2 miles +2817' -2860'

Day 3: It was only a slight drizzle as I moved through thick woods. Aggrieved that the chafing remained I held a hand on my groin and was relieved at the relief in the pain. I ran five miles like that, finally resuming a decent pace. I was overjoyed. Grinning. I had the solution, I gleamed, as I comfortably jogged along through woods that felt like home with one hand holding my two hiking poles and the other my shorts. Somehow I had the thought to adjust my shorts by rolling up the waistband to give myself a bit of a self-induced wedgie. With everything held securely in place, I stopped pretending to be Kilian Jornet at Hardrock (which he won with a dislocated shoulder) and resumed the more proper use of both arms. I share those chafing details because it was my reality and such seemingly minor frictions are the reality of runners attempting to cover this distance. I arrived at the next aid station quite pleased with my situation. Though cheerfully corrected the volunteers when they pretended to me that I was over halfway. While I had traversed the most ground I ever had in my life, the 102.5 miles was still shy of halfway because the deceptively named Bigfoot 200 would cover 206.5 miles.

Spencer Butte to Lewis River: 9.6 miles +1282' -2852'

A view of falls on Lewis River.

Jogged down the road then gingerly moved down steep trails to the river before heading back up along it, with gorgeous views of falls. Arrived at this station and refueled. The next section was a long one so I ate plenty—noodles and a burger.

Lewis River to Council Bluff: 18.9 miles +5472' -3315'

This section never ended. I’m still running it in my head. Along a creek. Serpentine. Up and down. Then just up as though no one knew what switchbacks were. But ah, the blueberries. At first I stopped to collect and consume but then tried to snag them as I lunged uphill. The blueberries were a mixed blessing. They - and my searches for them - were a tasty distraction but that distraction also forced attention away from my footing. I recklessly encountered more near ankle twists and uncomfortably sharp landings as I’d step on a rough stick or slightly trip over a snagging branch. Generally I had a sharp lookout on the trail. I’d sneak quick glances at the scenery but always pause before appreciating the real vistas. I’d wait for clear trail before taking a sip of water or stop entirely before fishing out a little baggie of gummy bears. After pain increased in the pads of my feet I tried to keep my eyes and hands from the blueberries. The trail suddenly crested and swung around and then down to the next station. Throughout the course the volunteers catered to our needs and dreams. Cooking up hot food to order. Here Richard Kresser, the winner of last year’s race, enthusiastically reassured me that the incredible views described in the runner’s manual were real. That, and the quickly falling light, pushed me out of that aid station much earlier and more optimistically than I’d planned or expected after the prior long leg.

Council Bluff to Chain of Lakes: 9.8 miles +1740' -1487'

The darkness fell much faster than I expected, or I was slower than I’d hoped, but despite missing the views of Adams at sunset I was still more than happy to have pushed through that aid station without much fuss. One of the hardest parts of the race was always the decision to leave the last aid station. I wasn’t considering dropping, but taking it too easy with too much time at the stations would result in the same. Once on a leg the task was clear: one sure step at a time. Time and steps would pass together. I made it into the next station well after dark after a long wide-open mountain road section with the stars exposed far above. I slept again in the back of my dad’s rig. My best and most real sleep of the weekend.

Chain of Lakes to Klickitat: 17.3 miles +3927' -3900'

Day 4: Only 65.7 miles to go - in four legs. A quick bit of hot food and fresh socks doubled up with some waterproof socks and, after being reminded about my headlamp strapped unnecessarily atop my head, I stepped out into the early morning light. I was excited about those wet feet river crossings the manual threatened. I was grateful for the safety line and my poles as I wobbly crossed one of the rivers with the current nearly knocking me off my feet.

A view of the mountain through the trees.

After the rivers the trail opened and headed back to higher elevation. I was disappointed that it became more exposed apace with the rising sun but again the views were sustaining.

A view of the mountain above the trees.

A view of the mountain beyond the trees.

I was aware there was a peak to climb to in another out-and-back and for a half-second assured myself what sat in front of me wasn’t it. Then of course it was. I very slowly stepped up the steep and gravelly trail to Elk Peak and briefly took in the view below the beating sun. Then cautiously moved back down to the trail and then down switchbacks to the next aid station. Here I dried my feet at a campfire, the rivers having been too deep for the waterproof socks to make a difference.

Klickitat to Twin Sisters: 19.4 miles +4919' -4987'

This leg stands particularly long in my memory in part because once it was over I knew the rest would finally feel fathomable. The route was incredibly well marked so while the trail faded here and there it was easy to stay on track. With this section we started to see scores of fallen logs, simply intentionally left to ensure that we stretched our legs a bit. In the pre-race brief the race director had dryly suggested we bring a step ladder.

A view of a mountain lake.

A view of mountain flowers.

While I love running on soft trails through dark Washington woods the limited line of sight produced a painful monotony and feeling of no progress. It was nice to have the fallen trees to break things up a bit. The marker indicating the start of the out-and-back to the next aid station finally appeared. 2.8 miles to go. Seeing other runners heading back out from the station was heart warming. Darkness fell quickly in those dark woods and I carefully placed each step, wary of the steep sloping sides down out of my sight. Finally pulled into the aid station. I ate plenty of food. My father helped me carefully replace or refill the necessary gear—water, socks, batteries, salt pills, baggies of gummy bears. Then I attempted to get 90 minutes of sleep. I was mighty restless but was raring to go when the alarm when off. I had only 29 miles left. 29 miles. Ha. Too easy.

Twin Sisters to Owen's Creek: 16 miles +2592' -4760'

Day 5: I set off at 0030. The elevation profile for this leg looks like it is a gentle downhill lope. This is a deception. There was the 2.8 mile largely uphill return to the main trail. Then I rolled through a trail densely overgrown with dew from the bushes reaching over it numbing my legs. After that the final out-and-back up a gnarled and rocky incline to Pompey Peak. I switched off my headlamp and stood there soaking in the view of Mount Rainier silhouetted by the countless stars with the snow reflecting the moonlight. I took my time returning from the peak, fully aware of the steep cliff sides. Then made my way through and over the trees down to an abandoned gravel road graciously covered in moss. In my excitement, and after at one point hearing a heavy rustling in the bushes nearby, I picked up my pace through to the final aid station. I was full of cheer and Geoff Quick at the aid station ensured I was fully of food and gratitude for the opportunity. I handed off most of the emergency gear stuffed in my bag: rain coat, rain pants, headlamp, spare flashlight, and batteries.

Owen's Creek to White Pass High School: 13 miles +385' -1639'

Then I jogged down the gravel road and, grinning ear to ear, came out on the road to see the morning sun beaming on the farms below. In phases I ran and then barely walked as I excitedly or with forbearance fearing injury approached the finish. I turned into the parking lot and then onto the track. I foolishly fought back tears as I ran three-quarters of the track and was glad I still had my sunglasses on as I crossed the finish line.

Image of my grinning finish with tearwelled eyes obscured from view by sunglasses (Howie Stern & Scott Rokis Photography).

## Gear * Vest: Nathan VaporCloud 2-Liter Hydration Vest. I did not use the bladder, but stuffed the back with emergency warm and wet weather gear and sundry other items. * Water: 2x CamelBak Podium Chill 21 oz Insulated Water Bottles in the front of my vest & SteriPEN Adventurer Opti. * Hiking Poles: Black Diamond Alpine Carbon Cork. These were used for many purposes. I used them the entire run. I used them for stability on downhills or near steep edges, sometimes for leverage on uphills but my thighs were generally fine (or it was a sign I was exerting too much). The most common use was to brush back all the brush and branches that crept over the trail. They were also consciously my last resort were I to encounter bigfoot herself. * Shoes: Altra Men's Superior 2.0 Running Shoe. I alternated through three pairs that my father cleaned and dried for me. * Socks: Injinji 2.0 Men's Run Original Weight Mini Crew Toesocks. By the last half of the race I was doubling up the socks. * Waterproof socks: RANDY SUN Unisex Waterproof & Breathable Hiking/Trekking/Ski Socks. These are heavy and hot, but suitable for most water protection. The river crossings were too deep for the socks to be of much benefit in this case except for extra padding. * Nipple protection: Large transparent bandages. * Fuel: HARIBO GOLD-BEARS gummy bears. Each 5oz bag was split into two baggies and enough baggies were carried on each leg to get an influx of ~250 calories every hour between aid stations.

Running and Training Lessons

I should test out thicker shoes and thicker socks. My toes and feet were generally fine, one small blister on that was no bother, but the pads of my feet ailed me considerably. I have never confronted such a chafing problem before. I will need to closely examine my shorts and the creams I use and put it all through the wringer by intentionally wetting them prior to long runs. Before running risk of hallucinations I do want to do practice runs to see my sleep deprivation limits. Generally I felt well-enough trained, despite not following through on much of my planned training. I had massively increased the amount of cross-training I did. I started doing hot yoga. I think this helped my breathing considerably (which I used to control myself) and my balance and alignment in my running postures. I also started walking a long route to school with a weighted vest. I think that as well as basic body strength exercises well-prepared me for carrying my vest with water and gear all those miles. Seeing the sores produced on the backs, necks, and shoulders of others, I was very grateful I’d well-tested my vest with race-like weight. Also, the unforgettable Mount Baker Ultra Marathon in June was fantastic training for sticking to even when you cannot move as quickly as you might like.

A Bigfoot-Griffin Tussle

A view of a griffin and bigfoot locked in a tussle.

The race director requires entrants to mail a Bigfoot ("can be a live specimen, a picture, stuffed animal, sticker, statue, clothing...just needs to be a Bigfoot") within one month of acceptance into the race. The items are then used in the award ceremony after the race. We also had to report what animal best represented us and why. I said griffin and claimed it was the sworn enemy of the bigfoot. For my item, I commissioned an artist on Etsy to draw "a sketch of a griffin crushing a bigfoot". At the award ceremony the runner with the best hallucination story, Jean Beaumont (3rd place woman; 75:54:28), won a framed version of this picture. I no longer think of it as a griffin crushing a bigfoot but rather as a tussle that will continue.

All photos by me unless indicated otherwise.